Exploring how good could it be to have a Cargo-like build system for C++ that simplifies the build & dependency management.

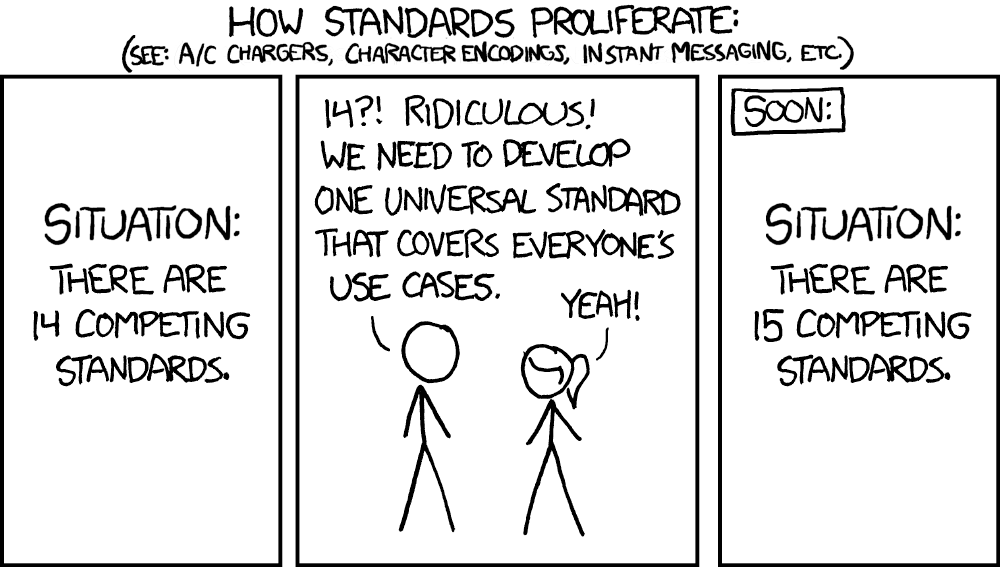

Possibly because of the age of the language and absence of a centralized standard, C++ couldn’t settle on a single all-encompassing build system. Instead, the community largely converged on CMake as a de facto standard. Having worked with it extensively, I’ve seen that it enabled lots of hard-to-see bugs and cognitive overhead.

Setting up dependencies often involve navigating another repository, understanding its build system intricacies, and then integrating it into your own CMake setup. It also has lots of different ways to do the same thing, which can further complicate both CMake evolution (because of the need to maintain backward compatibility) and user experience. We can’t blame it for everything, just like how the design decisions in space shuttle can be traced back to the two horses’ rear ends, CMake’s current state can be linked to the early design decisions made decades ago and the need for backward compatibility.

What’s Wrong?h2

Consider what happens when you want to create a simple executable:

cmake_minimum_required(VERSION 3.22)project(my_project)

set(CMAKE_CXX_STANDARD 20)set(CMAKE_EXPORT_COMPILE_COMMANDS ON)

file(GLOB_RECURSE SOURCES CONFIGURE_DEPENDS "${CMAKE_CURRENT_SOURCE_DIR}/src/*.cxx" "${CMAKE_CURRENT_SOURCE_DIR}/src/*.hxx")

add_executable(my_project ${SOURCES})target_include_directories(my_project PRIVATE "./include")

# Dependenciesadd_subdirectory(external/some_library)

find_package(Threads REQUIRED)target_link_libraries(my_project PRIVATE Threads::Threads some_target)We can see several issues here.

-

It looks imperative, we’re telling the build system how to build the project step by step: First, gather these files. Then, create an executable target. Now, add these include directories. Find a dependency and link to this library. It’s a sequence of imperative commands. But for most projects, we think about what to build instead of the mechanics of compilation. We think declaratively: “This is an executable project. It uses C++20. It depends on these libraries.” The implementation details—how to invoke the compiler, in what order, with which flags—shouldn’t be our concern.

-

Syntax is too verbose, requiring many lines and words for simple tasks. For one, we have to explicitly list source files. Setting the compiler standard also consists of multiple concepts (a variable, a property, etc.) that we have to juggle separately. Managing include directories and linking dependencies also involve multiple steps. This verbosity gives freedom and makes CMake powerful, but at the same time, it burdens users with unnecessary complexity, cognitive load, and enables foot-guns & hard-to-see bugs.

-

Dependency management is cumbersome. Adding dependencies often requires navigating to another repository, understanding its build system, and then integrating it into your own CMake setup. This process can be time-consuming and error-prone, especially for larger projects with multiple dependencies. We have concepts like

FetchContentandExternalProject, but they have their own quirks. We don’t have a unified way to declare dependencies and let the build system handle the rest, like Rust’s Cargo.

A Simpler Alternativeh2

In contrast, Rust’s Cargo demonstrates the power of declarative build configuration:

[package]name = "my_project"version = "0.1.0"edition = "2021"

[dependencies]serde = "1.0"some_library = "0.3"This configuration is purely declarative. We’re not telling Cargo how to build—instead we describe what the project is. Cargo handles all the implementation details: finding source files, determining compilation order, resolving dependencies. The difference is very noticable, especially as projects grow in complexity.

Valet: Bringing Cargo-like Simplicity to C++h2

Equipped with this vision, I felt an itch to build valet to explore how this declarative approach & easy dependency management could look like for C++. The goal is to have a build system that focuses on simple declarative configuration and easy dependency management.

Design Principlesh3

Here’s a simple mental model when starting a C++ project:

- “This is an executable” (not “call

add_executablewith these sources”) - “It depends on this library” (not “find a way to fetch the repository and figure out target names, find and link these targets, propagate these includes”)

With valet, it can be expressed as simple as:

[package]name = "my_project"type = "bin"version = "0.1.0"std = "c++20"Just like Rust’s Cargo, that’s the complete description. There’s no file globbing, no explicit target creation, no manual include path configuration. The user should declare their intent, and it should handle the rest.

The benefits of this approach become clear as projects grow. Consider adding a dependency:

[dependencies]eratosthenes = { git = "https://github.com/shamilatesoglu/eratosthenes.git", rev = "920417d0" }We shouldn’t need to think about:

- How to find the dependency’s build configuration

- What include paths to add

- Whether it’s a static or dynamic library (for most of the time)

- Which compiler flags to propagate

- In what order to build things

Whenever possible, it should try to infer from the dependency’s own declarative configuration. I should simply state the relationship, and the build system should construct the correct build graph.

This can be made possible by seeing the build configurations as relationships and properties instead of procedures. An executable has properties (C++ version, optimization level, etc.) and relationships (depends on library X). With declarative configuration, I’ve only specified the what. The build system is free to implement the how however it wants. This means improvements to the build system automatically benefit the projects without configuration changes.

Handling Real-World Complexityh2

Real projects aren’t always simple. Sometimes I need compiler flags, include visibility control, or platform-specific handling. valet provides escape hatches for these scenarios while keeping the common case simple:

[package]name = "my_project"type = "bin"version = "0.1.0"std = "c++20"includes = ["./third_party"]compile_options = ["-Wall", "-Wextra", "-Wno-unknown-pragmas"]

[dependencies]some_lib = { path = "./libs/some_lib" }remote_lib = { git = "https://github.com/user/repo.git", rev = "abc123" }The key difference from CMake is that these are still declarative properties of the project, not imperative build steps. When I say includes = ["./third_party"], I’m declaring a property of the project, not calling a function to modify some global state. The build system can use this information however it wants to achieve the desired result.

For dependencies, valet supports both local path-based dependencies and remote Git repositories. The syntax remains consistent and declarative—I’m just stating where the dependency lives, not how to fetch or build it.

This simplicity partially comes from limiting the freedom. valet assumes:

- Each project produces a single target (executable or library)

- Dependencies are either local paths or Git repositories

- No custom build steps or conditional logic

For this reason, valet in it’s current form, is rather for small-to-medium sized projects.

Current State and Roadmaph2

As an experimental project, valet has some basic features implemented:

- Static library projects

- Executable projects

- Git repository dependencies

- Parallel compilation

- Compilation statistics

compile_commands.json

Planned features include:

- Platform-specific configurations

- Test and benchmark targets

- Prebuilt library dependencies

- Compilation cache

- A remote package registry

- Precompiled headers

- Cross-compilation support

- Unity builds

- Extensible toolchain support (Only clang++ is used currently, and there’s no way to change compiler)

These features would be interesting to explore, feel free to contribute on GitHub.

Technical Challengesh2

Some technical challenges stood out while building valet. Apart from algorithmic challenges, the most significant challenge would be to support and work with existing build codebases seamlessly, which is not realized yet (if ever).

1. Dependency Resolutionh3

When users declare dependencies, I need to construct the correct build graph. This requires:

- Circular dependency detection

- Topological sorting for compilation order

- Transitive dependency resolution

- Automatic propagation of include paths and compile flags

2. Cross-Platform Supporth3

C++ compilers vary dramatically (GCC, Clang, MSVC). When a user declares std = "c++20", I need to translate that to the correct flag for their compiler (-std=c++20, /std:c++20, etc.). There are a lot of properties in the configuration that require similar translation.

3. Working with Existing Codebasesh3

Currently, valet only works cleanly with other valet projects. If it were to be widely adopted (if ever), it would have to work with existing tools and codebases. It should be trivial to switch from other build systems to valet. Its package registry should at least contain most popular C/C++ libraries and it should be easy to add/migrate more.

Usage on an Existing Projecth2

I’ve tried it on box2d, a popular 2D physics engine written in C++. By creating a simple valet.toml file and declaring the project type and dependencies, I was able to build it without modifying its source code. This demonstrated valet’s potential to work with existing codebases, although more work is needed to handle complex scenarios and edge cases.

[package]name = "box2d"version = "2.4.1"std = "c++20"public_includes = ["./include/"]includes = ["./include/"]type = "lib"Adding this valet.toml to the root of the box2d repository, a simple build command produces:

valet build --stats[ info ] Compiling (1/45) /Users/msa/Repos/box2d/src/dynamics/b2_joint.cpp[ info ] Compiling (2/45) /Users/msa/Repos/box2d/src/dynamics/b2_chain_circle_contact.cpp[ info ] Compiling (3/45) /Users/msa/Repos/box2d/src/dynamics/b2_weld_joint.cpp...[ info ] Compiling (43/45) /Users/msa/Repos/box2d/src/collision/b2_edge_shape.cpp[ info ] Compiling (44/45) /Users/msa/Repos/box2d/src/collision/b2_time_of_impact.cpp[ info ] Compiling (45/45) /Users/msa/Repos/box2d/src/collision/b2_distance.cpp[ info ] Linking (1/1) /Users/msa/Repos/box2d/build/debug/box2d=2.4.1/box2d

Source File Compilation Time (s)-------------------------------------------------------------------------------b2_chain_circle_contact.cpp 0.42b2_joint.cpp 0.34...b2_timer.cpp 0.11b2_block_allocator.cpp 0.08

Binary Link Time (s)-------------------------------------------------------------------------------box2d 0.14

Total time: 3.89 sPackage resolution time: 0.00 sCompilation time: 7.42 sLink time: 0.14 s

[ info ] Build succeeded (3.894985s)Closing Thoughtsh2

Building valet has been an exercise in exploring what declarative C++ build configuration could look like. CMake’s flexibility comes at the cost of verbosity and complexity for common tasks. Most projects just need to build an executable or library and manage dependencies—they don’t need to control every compilation detail. Focusing on what to build instead of how, could reduce cognitive load and boilerplate, making C++ development more enjoyable.

The source code is available on GitHub.